Black History Month Spotlight – Honoring the Past, Creating the Future: Interviews with Sara and Natalie Daise

Black History Month is an annual celebration of achievements and a time for recognizing the central role of African Americans in U.S. history.

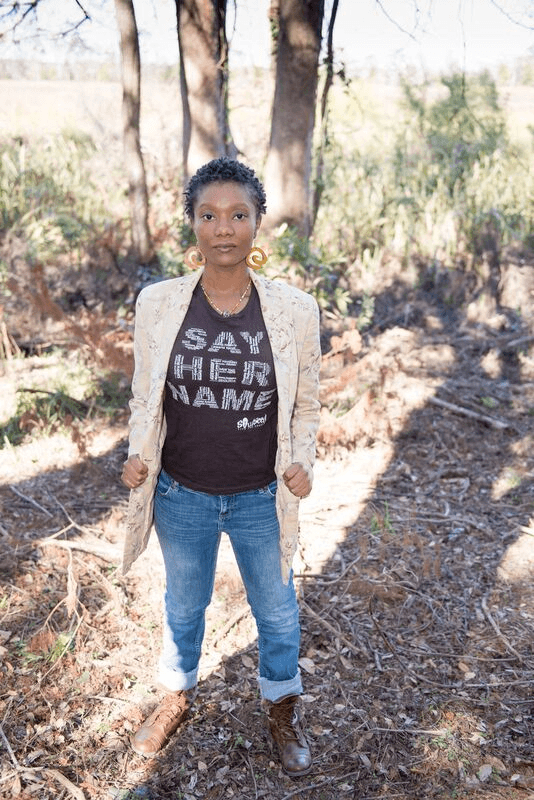

This week the spotlight shines the light on a mother, alumna Natalie Daise (2014 Graduate M.A. Creativity Studies) and daughter, Sara Daise (M.A. History & Culture student) who are using their creative skills and education gained through UI&U to honor the past and create the future in the Q&A below.[vc_raw_html]JTNDZGl2JTIwY2xhc3MlM0QlMjJhcnRpY2xlLWltYWdlLWJobS1kaXYlMjIlM0UlM0NhJTIwaHJlZiUzRCUyMmh0dHBzJTNBJTJGJTJGbWFraW5naGlzdG9yeWJ0dy5jb20lMkYyMDE2JTJGMDglMkYwNiUyRmluYWxpZW5hYmxlLXJpZ2h0cy1saXZpbmctaGlzdG9yeS10aHJvdWdoLXRoZS1leWVzLW9mLXRoZS1lbnNsYXZlZC1hdC1ob2JjYXctYmFyb255JTJGJTIyJTIwdGFyZ2V0JTNEJTIyX3NlbGYlMjIlMjBjbGFzcyUzRCUyMmNlbnRlciUyMiUzRSUzQ2ltZyUyMGNsYXNzJTNEJTIyaW1nLXdpdGgtYW5pbWF0aW9uJTIwYXJ0aWNsZWltYWdlYmhtbGVmdCUyMGFuaW1hdGVkLWluJTIyJTIwZGF0YS1kZWxheSUzRCUyMjAlMjIlMjBoZWlnaHQlM0QlMjIxMDAlMjUlMjIlMjB3aWR0aCUzRCUyMjEwMCUyNSUyMiUyMGRhdGEtYW5pbWF0aW9uJTNEJTIyZmFkZS1pbiUyMiUyMHNyYyUzRCUyMmh0dHAlM0ElMkYlMkZjb21tdW5pdHkubXl1bmlvbi5lZHUlMkZ3cC1jb250ZW50JTJGdXBsb2FkcyUyRjIwMTglMkYwMiUyRnNhcmEtZGFpc2UtMS5wbmclMjIlMjBhbHQlM0QlMjIlMjIlMjBzdHlsZSUzRCUyMm9wYWNpdHklM0ElMjAxJTNCJTIyJTNFJTNDJTJGYSUzRSUyMCUwQSUyMCUzQ3AlMjBjbGFzcyUzRCUyMmNhcHRpb24tYXJ0aWNsZS1iaG0lMjIlM0UlMjBTYXJhJTIwRGFpc2UlMjAlMjMxJTIwSGlzdG9yaWMlMjBJbnRlcnByZXRlciUyMGZvciUyMHRoZSUyMFNsYXZlJTIwRHdlbGxpbmclMjBQcm9qZWN0JTIwJTNDJTJGcCUzRSUwQSUyMCUyMCUzQyUyRmRpdiUzRQ==[/vc_raw_html]An Interview with Sara Daise (M.A. History & Culture student)

Q. What is your course of study and why did you choose it?

A. I’m studying Afrofuturism as a tool for addressing and healing generational trauma in Africana women.

Q. What is AfroFuturism?

A. There are many definitions. But I see Afrofuturism as a way of exploring and celebrating the existence of Black people through time. It’s about imagining a free, safe and empowered future. It is the recognition that we are the future that our ancestors dreamed, and our power and responsibility to create the future for our descendants.Q. How did you come to this study?

A. I’m a public historian. During my work as a historic interpreter at McLeod Plantation, in Charleston, SC and at The Slave Dwelling Project, and as an archivist with the Real Black Grandmothers, a project that is creating a digital archive of the remarkable and diverse experiences of black grandmothers and their grandchildren from past to present.I came to see history as alive and contemporary. To present history as stagnant felt inauthentic. As a 6th generation Gullah Geechee woman I was particularly interested in how my Gullah Geechee ancestors utilized Womanism as a form of resistance and survival during the Reconstruction Era. This interest was driven by my awareness of the harmful beliefs held by many of my contemporaries around areas of race, culture, gender roles and sexuality. During my research I came to understand that these beliefs have their genesis in the negative realities faced by Africana Women – slavery, patriarchy, toxic masculinity – both without and within the Black community. Now that I could see this, the question was, “what now?”

During the course of the study I was introduced to the field of epigenetics, which suggests that we may be manifesting generational trauma — that trauma is actually written on our DNA. There are many studies which support this. This blew my mind. It sounds like something out of Science Fiction. Actually, life in the United States often seems like Science Fiction! I then stumbled upon the field of Afro-Futurism and the deeper I went, the more I realized that this was not something new. And it might be a tool for finding a blessing amidst the trauma

Q. Who is a big influence in your life?

A. During this study I discovered the work of Malidoma Some, a West African scholar and mystic. His life work is Afro-futurism in practice, not just in theory. He writes a lot about presence — about being present. He states that it is within the present that the past and future meet. I am so inspired by his work and encouraged to practice presence even in the midst of chaos and crazy.

Q. How do you envision your work in the world when you finish your degree?

A. I want to create programs, materials and experiences that help others develop the tools that make our vision of the future — in which we are free, fearless, safe and whole — become the reality.

Q. Why did you pick Union?

A. My mother did her M.A. at Union and she suggested it. This program has allowed me the freedom to tailor my curriculum and study what I’m interested in. I am able to be myself in this program. I’ve found the professors extremely supportive and willing to give honest feedback. I’ve learned so much!

Q. What surprised you most about this journey?

A. I love citations! In undergrad they were a burden and I just didn’t get it. But I’ve come to see Bibliographies like maps that share the writer’s journey and provide breadcrumbs for others to follow. And it’s an honor to add my own work to the trail.

Q. Since the present is the place where the past and the future come together, what can you tell your 18-year-old self?

A. I’d tell me: “You are so dope. Instead of worrying about what others think of you, you can let the reality in your head become the reality all around you.”

An interview with Natalie Daise (2014 Graduate M.A. Creativity Studies)

Q. What do you call yourself? How would you describe yourself and your work?

A. I call myself a Creative Catalyst. Most of the work that I do has to do with empowering others to be more creative — whether that’s in terms of interpreting their own experience, or in using creative tools to brainstorm, solve problems, or improve the quality of their lives. I’m in love with the creative process and I want others to identify that within themselves. I want people to walk away from anything that I do recognizing their own creativity.

Q. Do you consider yourself a leader?

A. A leader is generally someone that others follow, right? I guess anyone who is able to be a catalyst for action, or facilitate a process of growth or discovery is a leader. And in that way, I am. People and groups that I work with are able to use my guidance to facilitate positive change. As an independent contractor, I work in many different environments. With early childhood educators and students, for example, I work with them to bring creativity in the process of their classrooms. I might work with church groups on developing community. If I’m working with a group on diversity or inclusion, I might help them find creative ways to look beyond “the other” and see themselves.Natalie Daise in Gullah Gullah Island, a TV show based on the Gullah Geechee culture which was passed on by enslaved West Africans who were brought to this country.I suppose I’m more of a servant leader. I’m not a directive leader unless that’s what’s called for. I adapt my techniques to the situation and environment. I have mastery in the ability to make connections—both for large groups and individuals. I can hear and see clearly what is there, and I have the skills to help others see it as well. I can say that I most definitely have mastery in the use of story to direct and shape experiences.

Q. As an alum, talk about your long relationship with UIU.

A. I actually received my undergraduate degree from the ADP at Vermont College in 1992—Vermont College was later absorbed by UIU. I laugh at the evolution of distance-learning programs. At Vermont, every semester we did do some residency in Montpelier, Vermont. Our class discussion, peer-feedback, and inter-library loans were all sent via snail mail. A lot has changed!

My undergraduate thesis explored the healing power of story. I went into the program with the intent to focus on history. I wanted to get the academy’s validation to continue the historical and cultural preservation work my husband I were already doing. I thought a degree would help me call myself a historian without flinching.

Prior to this experience, my view on education was basically “get a degree you can sell.” An education existed as a marketable commodity. It was in that program, however, that I kept hearing people talk about “following their passion.” I had never ever thought about education as it pertained to my passion. I was intrigued. For the first time I thought of education as something one does for oneself as well. And so I switched to a writing focus.

Q. Are there connections between your undergraduate and graduate theses?

A. As an undergrad I was really interested in the power of story to heal and connect. I read amazing writers, mostly women of color, who were also healers, activists, organizers, and influencers. I was interested in how they used writing as a tool for their work. I was a professional storyteller prior to this research. But after that, I approached story differently. Stories are real things. Everything is story! When we change the story, change the narrative, we change the perception. The story tells us who we are as a country. The story tells us who we are as women. The story tells us who we are as individuals. What stories are we telling about ourselves? About each other? Which stories have shaped our belief system?

Natalie in Becoming Harriet Tubman

When I went back to graduate school to study the process of creativity, I went in with the question of ‘Becoming.’ In many ways creativity is the process of becoming. It’s that process by which an idea becomes a thing. The process by which we move from one phase of something to another. Whether that idea becomes a painting, or a building, or a person. And there’s a story about that.

I actually came across my undergraduate thesis about 20 years later as I worked on my graduate thesis. And I was surprised to see how my undergraduate work had led me in this direction and the connections between my interest in story and in creativity.

Q. What was your process like studying Creativity?

I had excellent instructors, but as I read the assigned texts and did the research, I noticed that I wasn’t there. Even the way creativity was defined seemed to exclude me. And yet, quite honestly, I’m one of the most creative people I know. When creativity specialists wrote about the environments and conditions out of which creativity arose, those environments and conditions didn’t apply to my ancestors. Or most women. Or many people of color. As a matter of fact, I could hardly find any people of color in any of my studies. It was like I was invisible. So this changed how I approached the study. I had to say, “Where am I? And are these definitions even accurate?” I found myself searching outside the discipline of Creativity to look for myself, both as a woman, and as a person of color. And I’d find that when I would bring this information back, I was presenting my professors with material that was often new to them. In ways I was bushwhacking my own path through this study. I felt—after awhile—that my process wasn’t only to explore this, but to also educate those with whom I was working. To borrow a phrase from you, “to leave breadcrumbs for others to follow.”

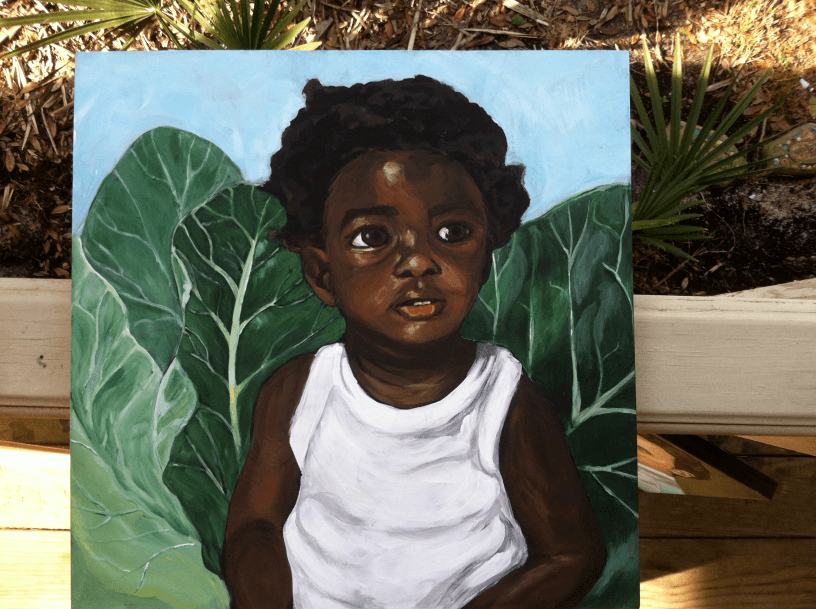

My thesis was very personal. It was an exploration of women artists of color in the Charleston, SC and how their creativity impacted their communities. I called the study “Rag Quilts and Collard Greens.” It felt important to study the interaction of creativity and community. So often, traditional arts are considered non-creative. Quilting, for instance, is considered just a necessity. You know, something women did at night with scraps. But I looked at the Gee’s Bends quilts and I thought, “Yes these women were in extreme poverty. And yes, these quilts kept them warm. And these quilts are also brilliant, and beautiful, and played a role in community survival. They were more than functional. They filled a need to create. Hopefully my thesis work adds to the dialogue and maybe others will begin to look at creativity in a way that explores other avenues. It’s really great to read what “the great men” have said about creativity. But that’s not the only story. Once again, who’s telling the story? I want to add to the narrative.

Q. How do you see your time and work at Union impacting your creative work post-graduation?

Everything changed. But during the grad program my visual art evolved by leaps and bounds, particularly in terms of how I tell stories with my art. And I will say that graduate school has obviously given me the credentials to back up the work that I do. This is the work of my heart, but it’s nice to say, “you should listen to me because I have a graduate degree in this process.” That’s important.

I’ve always been fascinated by the evolution of becoming. Even before I did my undergrad. But I didn’t think that how my mind worked, and what was interesting to, me was important to the world. That my passion was important. And yet, it is for me the most important thing. Going through this educational process has validated my uniqueness. And when I take this passion out into the world it has an impact on other people, I love that.

Q. Talk to me about what you’re working on now

A. I’ve recently developed a program called “Art is a Problem I Can Solve.” It’s about using our creative tools and skills to address our challenges. And there are many different ways to do that. I love facilitating hands-on creativity workshops in which we use art-making and apply the process to whatever the situation or challenge may be.

I am also working on a project with my daughter, Sara, in which we use story, ritual, and our own dialogue to explore multigenerational sharing and how we create ritual that we can pass on and create for the future.

And I continue to grow as a visual artist. I started working on The Collard Green series in 2013 while writing my graduate thesis. More than 25 paintings later I may have completed it. Wow. I can’t believe I just said that! I may have come to the end of the series. My visual art has continued to unfold and I follow it. More collard greens might pop up. But I don’t want to feel like they have to be there.[vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner column_padding=”no-extra-padding” column_padding_position=”all” background_color_opacity=”1″ width=”1/2″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner column_padding=”no-extra-padding” column_padding_position=”all” background_color_opacity=”1″ width=”1/2″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner]

Q. I know as a Black storyteller, your work is often heavily requested during Black History Month. Can you talk about the relevance of your work beyond February?

My history as a Black woman is everyone’s history. I’ll always be a Black woman. But I don’t know that if that’s the most important thing about me. Yes, it impacts my experience in the world. I love all my beautiful brown-ness. But I hope that what happens when I give a talk, or facilitate a workshop, or when I tell stories—I hope that we see in each other our humanity. That’s what I hope. That’s my desire always.

Q. What would you tell 20-year-old Natalie?

Man. 20 sucked. At 20 I thought I was trapped in my fundamentalist religious community, I didn’t know I could have a different life. I was still trying really hard to live the life that had been mapped out for me. I’d say, “You are so much more free than you think you are. This idea that you’re trapped is just an illusion. There’s the door. You can go through it any time you want. You can create any life you want.”